What is Contemplation? | Christian Contemplative Practice FAQ

- The Contemplative Society

- Feb 16

- 5 min read

Updated: 7 days ago

Contemplation is the heartbeat of the Christian wisdom tradition. It is a word that carries the weight of centuries of prayer, silence, and the earnest search for union with God. Yet, even for dedicated practitioners, its precise meaning can sometimes remain elusive. Is it simply deep thought? Is it different from meditation?

For The Contemplative Society, contemplation is not a fleeting trend, but the anchor of our community. It is a grounded, ancient, and quietly radical way of being that reshapes how we experience the world, the Divine, and our own interior lives. This article will explore this word and all its depths.

Skip to the section you are looking for...

Defining the Indefinable

Let’s start with a few definitions to get our bearings.

Merriam-Webster defines it as "a concentration on spiritual things as a form of private devotion" or "a state of mystical awareness of God’s being."

Richard Rohr puts it more poetically: “Contemplation is a long, loving look at the Real.”

Cynthia Bourgeault, our founding teacher, often refers to contemplation not just as a practice, but as "luminous seeing"—a higher mode of perception that allows us to see reality as it truly is, connected and whole.

At its heart, contemplation is the practice of being fully present, in heart, mind, and body, to what is. It is a way of knowing that moves beyond judgment, analysis, or critique into a holistic, heart-centred receptivity.

The Story of a Word: From Temple to Living Tradition

To understand what contemplation is, it helps to look at where the word comes from.

The English word "contemplation" is derived from the Latin contemplatio, which is rooted in the word templum (a temple). But originally, a templum wasn't a building; it was a sector of the sky or a piece of ground marked out by an augur (a seer) for the observation of signs. To "contemplate" literally meant to create a cleared space for seeing.

In the Greek Christian tradition, the equivalent term is theoria, meaning "to behold" or "to gaze upon."

For centuries, this "gazing upon God" was largely seen as the domain of monks and nuns living in cloistered monasteries. But in the 20th century, a shift occurred. Following the Second Vatican Council, a desire emerged to retrieve these ancient practices for everyone, not just the "religious professionals."

This gave birth to what we now call the New Contemplative Movement:

In the 1970s, Trappist monks like Fr. Thomas Keating, Fr. William Meninger, and Fr. Basil Pennington developed Centering Prayer to make the contemplative experience accessible to laypeople.

In 1987, Fr. Richard Rohr founded the Center for Action and Contemplation (CAC) in New Mexico, cementing the idea that inner stillness and outer social justice are two sides of the same coin.

In 1997, The Contemplative Society was founded in British Columbia, becoming a hub for this growing network of practitioners.

Today, "Contemplative Christianity" has matured into a living, ecumenical tradition. It is a "monastery without walls," uniting people across denominations (and even those with no denomination) who are seeking depth, transformation, and a direct encounter with the Divine.

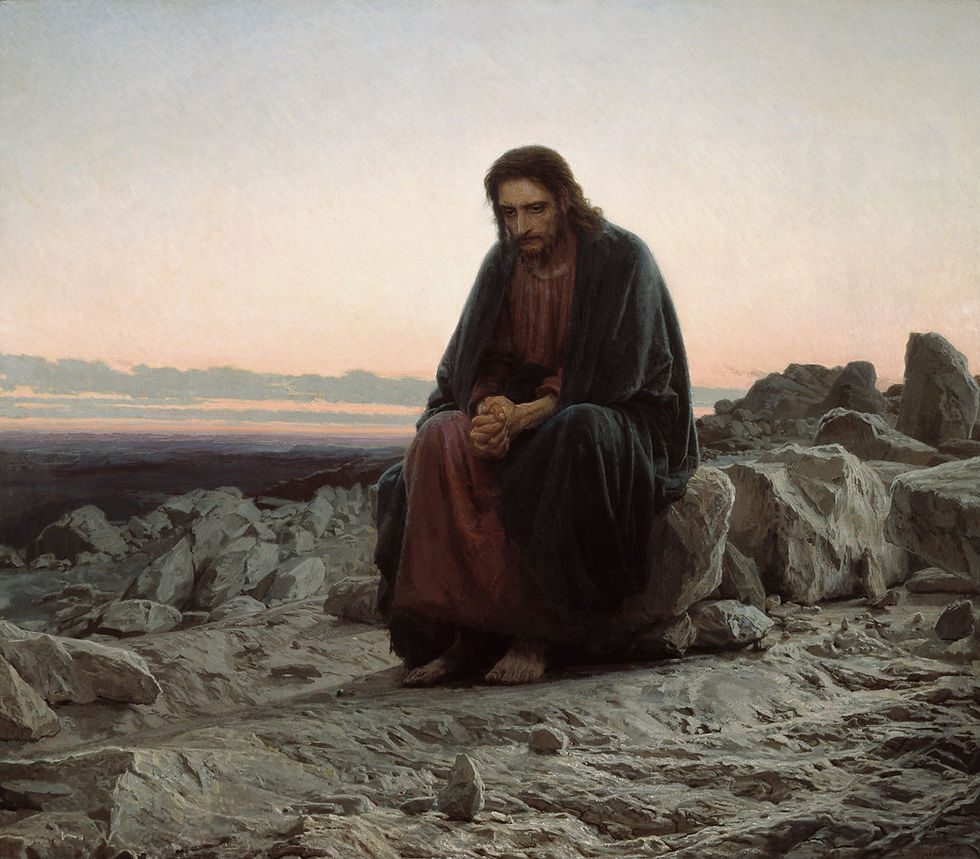

While the movement is modern, the roots are ancient. It begins with Jesus, who frequently withdrew to solitary places to pray in silence. In the Sermon on the Mount, he taught his followers to enter their “inner room” to commune with God in secret, a powerful metaphor for the inward stillness at the heart of contemplation.

This interior way was passed down by the Desert Fathers and Mothers of the 3rd and 4th centuries, who sought God in the silence of the Egyptian and Syrian deserts. It was preserved by monks like John Cassian and later codified in the medieval classic The Cloud of Unknowing, which taught a method of reaching God through loving surrender.

What Makes Christian Contemplation Unique?

Although Christian contemplation bears external similarities to mindfulness (sitting in silence, focusing attention), its theological heart is distinct.

It is Relational: Contemplation is not about self-optimization or emptiness for its own sake; it is about communion. The practitioner seeks to surrender the self in loving trust to the indwelling presence of God. It is a relationship.

It is Transformational: The goal isn’t just tranquillity or stress reduction (though that is often a byproduct). The goal is to put on the "mind of Christ." As we practice letting go of our own thoughts and agendas, we slowly become more compassionate, more grounded, and more capable of service to the world.

The Practices We Support

At The Contemplative Society, we support a "Wisdom" approach to Christianity, one that emphasizes practice over dogma. While there are many ways to pray, these are the core practices we teach and resource:

Centering Prayer: A method of silent prayer that prepares us to receive the gift of contemplative prayer. It involves the use of a "sacred word" to gently release thoughts and return our intention to God's presence.

Visio Divina: "Divine Seeing." A practice of praying with visual images, such as art, icons, or nature, inviting God to speak to the heart through what is seen, rather than just what is read or heard.

Lectio Divina: "Divine Reading." A traditional Benedictine practice of scriptural reading, meditation, and prayer intended to promote communion with God and to increase the knowledge of God’s word.

The Welcoming Practice: An "active" practice designed for daily life, helping us physically and energetically process emotions and sensations rather than repressing them, allowing us to remain present to God in the midst of turmoil.

Sacred Chant: Using tone and sound to drop the mind into the heart, often utilizing the Psalms or simple, repetitive phrases to anchor presence.

Liturgy: Contemplative Liturgies invite us to enter sacred silence through prayer, chant, and stillness in communal experience.

The Invitation

For many of us, the search for a spiritual path can feel like a need to "pick a team" or find the "one right system." You may have dabbled in Zen, Yoga, or non-dual traditions and found great beauty there.

Christian contemplation does not ask you to reject wisdom found elsewhere. Instead, it offers a way to return to your roots; to find that the stability, structure, and depth you seek have been present in the Christian tradition all along.

Contemplation is not about superiority. It’s not about claiming that this path is the only path. But it is a method that holds the deep, transformative "juice" that the human soul longs for. To be a contemplative is to cultivate presence, spaciousness, listening, and interior freedom.

We invite you to explore this way of being with us.

Resource Suggestion

Foundational Texts

The Cloud of Unknowing (Anonymous)

The Conferences by John Cassian

Interior Castle by St. Teresa of Avila

Modern Introductions

The Wisdom Way of Knowing by Cynthia Bourgeault

Centering Prayer and Inner Awakening by Cynthia Bourgeault

Open Mind, Open Heart by Thomas Keating

Into the Silent Land by Martin Laird

Everything Belongs by Richard Rohr

*Curated by Nicholas Fournie, Communications Coordinator, The Contemplative Society

PO Box 23031, Cook St. RPO

Victoria, British Columbia

Canada, V8V 4Z8

Copyright © 2025 - The Contemplative Society. All rights reserved.

Comments